Disclaimer

This page synthesises general information to help Indigenous communities, scholars, curators and auction houses identify historical message sticks more effectively. In most cases we do not have the authority to interpret Indigenous objects, make recommendations about them, or facilitate access to cultural authorities.

Background

Because message sticks are so diverse, they cannot easily be identified on the basis of visual characteristics alone. They can be very short, very long, flat, convex, cylindrical, notched, painted, feathered or burned. They can also be subtly repurposed from other objects such as spearthrowers or digging sticks.

Words for ‘message stick’ survive, in record form or living usage, in at least 87 Australian languages. This Indigenous lexical evidence is crucial when it comes to distinguishing message sticks from other objects that are classified differently.

‘Message sticks’ according to Indigenous definitions, are intrinsically public objects. They are created in order to be seen, often at a distance, by all kinds of public witnesses including strangers, women and uninitiated boys. A central function of a message stick is to communicate the right of the messenger to travel outside of their traditional country without fear of harm. This is why messengers often carried the message stick in a very visible way – hanging from the tip of a spear, in a headband or in a waist girdle. Of course, other secret objects might have also been carried by messengers, carefully wrapped and hidden from general view. However these items would be referred to with a separate term in the language of the messenger and would not be identified as a ‘message stick’.

Message sticks go by various names in English and Aboriginal English. ‘Message stick’ is the most common but in the Top End ‘letterstick’ is preferred. An archaic English term is ‘yabber stick’, not to be confused with ‘paper yabber’, a term that some Aboriginal messengers applied to pen-on-paper letters. In German commentaries it is a Botenstab (‘message stick’) or less commonly a Zeichenstab (literally ‘sign stick’). In Italian sources it is bastone messagio (‘message stick’) and in French bâton message (‘message stick’) and bâton parlant (‘talking stick’).

In a few collecting institutions there are instances where an item labelled with an English or European term for ‘message stick’ is placed in a restricted category. There can be a number of good reasons for this. It might be that the item has been subsequently sacralised by its traditional owners, perhaps because of its contemporary significance or cultural associations. Or it might be attached to string that is spun from human hair, and is thus classified as human remains. Or its status may be ambiguous. In some rare cases it may be the result of a historical misidentification: it is either sacred (and thus not a ‘message stick’) or it is a ‘message stick’ (and thus not sacred). More on this problem is below.

Two foundational criteria for identification

- Context: The primary criteria for identifying any object is through knowledge of its specific context: who made it, where, and for what purpose; and who today has the cultural authority to comment on it. This contextual knowledge might exist in the form of memory or oral narrative in the site that it was created. Or it may be retrieved from archival documentation in the form of notes, diaries, letters, books, or detailed museum records. In summary, an object is a message stick if there is reasonable evidence that it was used in a known communicative interaction, or that it was manufactured with the intention of replicating such an object. Tiny details can be very important. If a record contains a date as well as a location, it may be possible to find better-documented objects from the same time and place in order to compare it. Some of the most reliable contextual evidence is when an Indigenous term for ‘message stick’ is associated with the object, meaning that the researcher can defer to an Indigenous definition and not make inferences beyond this semantic scope.

- Formal characteristics: In the absence of direct knowledge from Traditional Owners, or solid archival evidence, an object may be provisionally identified as a message stick from its formal and material characteristics. Even though there is wide diversity of shapes and modes of marking, not all forms are equally likely. Prototypical message sticks are made of wood, are about 15 to 30cm long, have smooth edges, and are usually convex or cylindrical with tapering at one or both ends. The most common form of marking on a convex message stick is notches along the long edges, or repeated vertical grooves on its flat surface. Other common markings on all message sticks are diagonal crosses, isolated vertical lines and stippling (more common on cylindrical sticks). Message sticks marked only with paint are known in Arnhem Land. Elsewhere, a message stick may sometimes be finished with white or red ochre. In the absence of contextual knowledge, these common characteristics will not necessarily be enough to positively identify an object as a message stick but they will help constrain a judgment.

How to tell the difference between a message stick and a tjurunga (churinga)

Tjurungas (sometimes spelled ‘churingas’) are sacred objects from Central Australia and parts of Western Australia that are the exclusive property of initiated men. Traditionally, they should not be seen by women or uninitiated boys. In some communities of Central Australia, tjurungas became de-sacralised in the early twentieth century meaning that they became fully public and unrestricted. In other communities they remained sacred. There are also places where they have been de-sacralised and later re-sacralised. In the 20th-century, the tjurunga tradition spread west across the Western Desert and northwest into the Kimberley. To this day, tjurungas remain sacred and highly restricted in the Pilbara and the Kimberley.

Tjurungas are sometimes quite similar in appearance to message sticks, but while message sticks are highly public and secular, this is not always the case for tjurungas. This means that special care must be taken to distinguish the two objects. Tjurungas should never be displayed or sold without careful and thorough consultation with Traditional Owners. Even if tjurungas from a specific community are not considered sacred, they may be evaluated differently in other contexts.

Certain settler ethnographers in Western Australia, including Daisy Bates, and Roland and Catherine Berndt, knew the difference between tjurungas and message sticks but they had an unfortunate tendency to use the ‘message stick’ (or ‘letter-stick’) to refer to both kinds of objects. In some cases this mischaracterisation was deliberate. Bates, for example, was known to hold public message sticks in her possession yet represent them as sacred in order to increase her status in the eyes of both settlers and Indigenous communities. When it comes to Western Australian objects that are associated with these scholars, a handy way to know whether they have been mischaracterised is if there is any surviving detail on the identities of senders or recipients, eg, “Sent by Billy to his wife”. By definition a tjurunga is never ‘sent’ but remains the exclusive property of an initiated man. By contrast, a sent object is understood to enter into a public and witnessed interaction.

Misidentification (and deliberate mystification) of message stick technology continues to haunt collecting institutions in Western Australia and can have unfortunate repercussions for communities in terms of truth-telling and restitution. On the whole, museums elsehwere have been very good at labelling message sticks and tjurungas correctly, making sure that secret items are not displayed to the public and that public objects are not relegated to an oubliette. Sometimes collecting institutions can be overly cautious to the extent that certain desacralised objects may be more sacred to the museum workers than they are to their cultural owners.

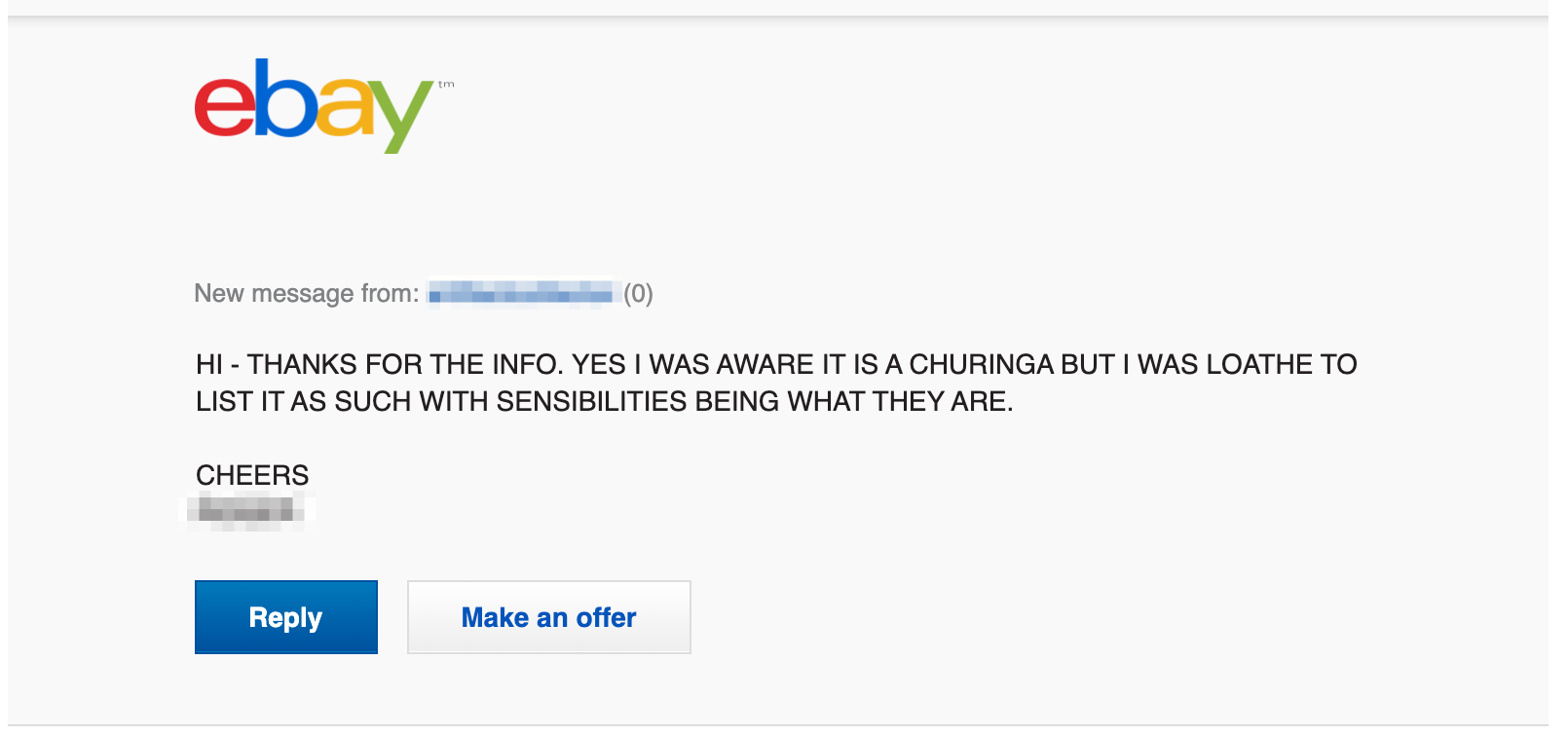

Auction houses and ebay traders, on the other hand, are notoriously irregular, often advertising tjurungas for sale as ‘message sticks’. Occasionally this is a simple mistake but sometimes it is clear from the description that an auction house knows that the the object in question is sacred, yet insists on labelling it a ‘message stick’. Many if not most of the tjurungas that circulate on the market are replicas of traditional tjurungas, made by Aboriginal people to serve the collector market. This does not make them inauthentic nor does it absolve auction houses from their responsibilities to label objects appropriately and prevent the public display of sacred designs.

The differences

To avoid violating cultural proscriptions, no restricted images will ever be displayed on this site. The written descriptions of the differences will be as generic as possible, but if you are sensitive about learning these distinctions please read no further. This information is intended to inform good practice and prevent distress. The information here is provided by Piers Kelly who has unintentionally acquired experience identifying tjurungas simply because he has read enough unedited ethnographic literature, and been exposed to so many badly labelled items that in some instances he can make a judgment. He is not the arbiter of what the objects mean nor of how they should be conserved or circulated – this is the exclusive right of Traditional Owners.

On the whole tjurungas tend to be larger than message sticks, and they are always flattened or slightly convex. They are almost always basically symmetrical, and well polished with long tapering at each end. Some are wider and more ovoid, like a shield. They are never notched but have very carefully executed and regular designs on their flat surfaces. A typical Central Australian design involves a series of evenly spaced and evenly sized concentric circles linked by sets of parallel vertical lines or divided by horizontal vertical lines. Other common motifs include parallel meandering lines or semi-circles. A typical design from the northwest of Western Australia involves a pattern of concentric diamonds or concentric squares taking up most of the surface of the object.

A good resource for understanding the history and context of tjurungas is:

- Anderson, Christopher, ed. 1995. Politics of the secret. Sydney: Oceania Monographs. It does not contain or reveal any restricted knowledge.

Another excellent read is:

- Batty, Phillip. 2006. White redemption rituals: Reflections on the repatriation of Aboriginal secret-sacred objects. In Moving anthropology, edited by E Kowal and G Cowlishaw, 55-63. Darwin: Charles Darwin University Press.

If you have cultural rights to access this material, you will find descriptions and images of tjurungas in the following historical texts. Please note that these are publicly available online but they have not been edited for cultural sensitivities. Extreme care should be taken in reading or circulating the materials. We point to these resources only that others with the right authority can be guided towards making better decisions about access, handling and conservation. We do not personally endorse the details of these texts nor approve of their publication and sale. We nonetheless respect the decisions of archives to maintain them and to manage access according to their own protocols.

- Campbell, W.D. 1911. The need for an ethnological survey of Western Australia. Journal of the Natural History and Science Society of Western Australia 3 (1):102-109.

- Clement, Emile. 1904. Ethnographical notes on the Western-Australian Aborigines: With a descriptive catalogue of a collection of ethnographical objects from Western Australia by J.D.E Schmeltz. Internationales Archiv für Ethnographie 16 (1/2):1-29.

- Jagor, Fedor. 1879. Ein Steinmesser und sieben Zauberhölzer aus Süd-Australien. Verhandlungen der Berliner Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte 11:105-106.

- Ratzel, Friedrich. 1894. Völkerkunde. 2 vols. Vol. 1. Leipzig und Wien: Bibliographisches Institut., p349

- Spencer, Baldwin, and F.J. Gillen. 1899. The native tribes of Central Australia. London: Macmillan & Co.

- Spencer, Baldwin, and F.J. Gillen. 1927. The Arunta: A study of a Stone Age people. London: Macmillan & Co.

A note for private collectors and auction houses

Sale of tjurungas is regulated under the Federal Moveable Cultural Heritage Act. If you believe you have tjurungas in your collection and you wish to return them to the control of their cultural owners and ensure their long-term preservation, please make contact with the National Museum of Australia or the Return of Cultural Heritage team at AIATSIS.

Although our priority is to work with First Nations communities and museums we are nonetheless happy to examine images of objects in your care to help you make better labelling decisions and to narrow down provenance. We cannot, however, provide ‘expert’ guidance with the aim of increasing an item’s commercial value, per principle 3 of the SAA code of ethics.