Message sticks are wooden objects that were once used widely for long-distance communication across Australia. A sender, usually a man, would orally compose a message to be delivered to a recipient living at some distance on the other side of a political boundary. He would first appoint a messenger and begin carving a message stick, explaining how the signs on the stick related to the spoken message. The messenger then carried the object to its intended recipient and reproduced the message orally while pointing to the relevant marks. The recipient might then carve a response message stick as a reply to the original sender.

Although this communicative routine appears to be straightforward it is deceptively powerful. From a functional perspective the message stick system performed at least four of the central tasks that today we tend to associate with writing: it stored information accurately, it aided recall, it permitted non-synchronous communication over time and distance, and it provided a visual means of authenticating a reported statement. Yet, unlike writing, the marks on message sticks did not model linguistic structure and the sign-repertoires themselves were open-ended and changeable. Moreover, the marks did not always make sense on their own because they were designed to complement an oral message supplied by the messenger.

Message sticks and writing

Does that mean that message sticks are fundamentally different from writing? In archaeological timescales, writing has only been with us for a split second, having first been invented 5000 years ago, and reinvented a handful of times since then. For much of its early history it wasn’t even fully exploited for asynchronous communication. Typically it has been used in face-to-face contexts with a good deal of orality to back it up, for example in reciting already memorised prayers and songs, or confirming material transactions. In other words, writing has often operated in a similar way to message sticks. Even today, there are many situations in which orality is foregrounded and literate practice occupies a supporting role. Think of the way news anchors read off teleprompters, or public speakers give text-heavy Powerpoint presentations. Other contemporary literacy events, like responding to bills, are seemingly grounded in writing but may not rely on any actual reading. Such comparisons reveal that non-written systems of graphic communication are much more powerful than they at first seem.

Although Indigenous messengers began encountering British and other settlers from the late eighteenth century onwards, it took some time for the newcomers to notice and remark upon their system of long-distance communication. The very earliest settler reports of message stick communication date from 1840 in the vicinity of Queanbeyan but it was not until the 1880s that message sticks became discussed and debated in public settings. Many scholars in Australia and Europe became intrigued by the possibility that they embodied a previously unrecognised form of Indigenous writing. This hypothesis was explored in newspapers and specialist journals, and soon a unanimous view emerged that the marks on message sticks did not encode linguistic meaning, at least not in any consistent way. Yet the archives are replete with baffling examples of message sticks sent and interpreted without a messenger at hand to provide an oral gloss, for example, after a messenger died en route, or when an accompanying verbal message was deliberately withheld to test the interpretive skill of a recipient. For some time, Indigenous people were also known to send message sticks through the regular mail, a fact that presupposes their interpretability without any oral support. In certain situations, settlers themselves treated message sticks as authoritative ‘texts’, for example, in the case of a message stick brought and ‘read’ as evidence in a criminal inquiry. Indigenous people, too, recognised a functional affinity between message sticks and writing: a common Aboriginal English term in the Top End is ‘letterstick’ and in the Ngarinyin language of the Kimberly the term for ‘message stick is paŋarati, a word the later extended to mean ‘book’.

How message sticks convey meaning in practice

If message sticks do not encode language, how is it that they could be ‘read’ even without a verbal explanation? This is a central puzzle that remains unresolved, but there are a few key elements that gave message sticks communicative force. First, there are a finite range of topics that a message stick can ever be about. Most commonly it encoded an invitation to ceremony, such as young men’s initiation or a funeral. There were also messages that involved coordinating people for hunting, declaring war or solidifying political alliances. Others were requests for items of value. All this means that when a messenger approached a camp, the recipient of the message would already have had an idea about what the relevant thematic parameters were. The messenger’s body could also have been painted up in a particular way, for example, they might be decorated in white ochre or pipeclay to signal the beginning of mortuary rites. Messages were typically from a specific named individual to another specific individual, further constraining the common ground between them and limiting the possible topics of communication. In Aboriginal Australia, kinship and social categories can regulate the kinds of things you can talk about as well as the way you are expected to talk about them. There are constraining conditions, in other words, imposed by the identities of the sender and the recipient and their prior relationship. All of this may be known even before a recipient sees the message stick itself, let alone interprets its marks.

The marks on a message stick were often very abstract notches, lines and dots. Their meanings were multivalent too. A simple notch frequently stood for a person, but it could also be a place, a countable object or an element in a narrative. A large part of my work research is about trying to isolate signs and their meanings and figure out what general class of information is being encoded through what channel. What topics are conveyed in the verbal message or with gesture? What is recorded on the stick? What is entirely unspoken and implicit? How are the various semiotic modalities orchestrated?

Changes to the system in the colonial era

The message stick routine varied from place to place and has changed in significant ways since the British occupation of Australia. In the early 20th century, for example, it became increasingly common for women to send messages, or for the sender and messenger to be the same person. Other adaptations include the use of iron tools in their manufacture, the exploitation of non-native or salvage timbers, Western influences in the motif system (alphabetic letters, playing card suits, rules of perspective, new pigments such as blue), and introduced methods of transporting message sticks such as by horse, steamer, coach or aeroplane.

Beginning in the early 1950s, message sticks began to be deployed for their political symbolism in settler–Indigenous negotiations. The earliest recorded instance of this is a message stick sent from Bathurst and Melville islanders to Prime Minister Robert Menzies in 1951. Today, message sticks are increasingly seen in high-profile public events where their role is to serve as symbols of cooperation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous institutions. Message sticks are also manufactured as artistic products for sale in Indigenous art economies. Meanwhile, the more traditional pre-colonial routines have disappeared from view, and were last recorded in Australia’s Top End. Message sticks were used in a traditional way in the Tiwi Islands until the 1950s, on Groote Eylandt until the 1960s and in Arnhem Land as recently as the 1970s.

Fieldwork

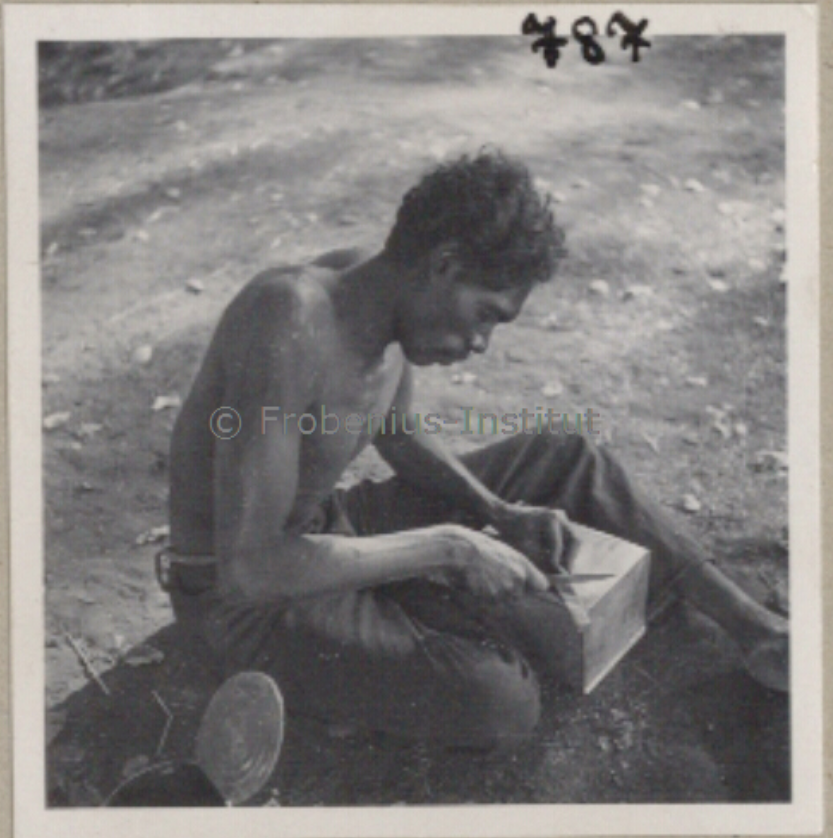

Even though no fieldwork on message sticks has been carried out since C. P. Mountford recorded their use in the Tiwi islands in 1954, message sticks continued to be sent in various parts of the Top End, especially Arnhem Land where they are referred to in Aboriginal English as ‘lettersticks’; a common term for them in local languages is mak. The Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (MAGNT) conserves several lettersticks from the Bininj Kunwok speaking area that were sent in the 1970s. Other letterstick communications from this region are recorded in archives and published oral narratives. In late 2019, BB [recently deceased] and Lena Yarinkura, two Kune-speaking landowners living on Angabarrbirri outstation, began documenting traditional message stick use. These two specialists demonstrated methods of manufacture, inscription and interpretation, and the results have been archived by Maningrida Arts. This is the first time the practice has been specifically documented in 65 years. More documentary work is proposed in Arnhem Land in 2023.

The global importance of message sticks to the study of visual communication

Although writing has become a very influential graphic code since its earliest invention five millennia ago, other systems of graphic communication have pre-dated writing and coexisted with it. Across the world, notionally ‘non-literate’ societies use a surprising range of graphic codes to solve problems and coordinate tasks. Accurate codes are used for such purposes as keeping accounts, marking calendrical time, structuring ritual recitations or supporting the recollection of spoken messages. Many of these systems remain poorly understood, having been abandoned or suppressed before specialists could pass on their knowledge. Since message sticks have been used for communication within living memory, there is an opportunity to understand the system properly and to compare it with other documented methods of information storage and retrieval developed in different cultural settings. Such work will encourage a better understanding of graphic codes while underpinning contemporary research into the cognitive and cultural-evolutionary dimensions of human visual communication.

To learn more

Those who wish to understand more about message sticks should consult this very short reading guide to research on Australian message sticks, pointing to the most important texts on the subject.

Honours or Masters project

I am also seeking Honours or Masters students who wish to write archives-based dissertations on message sticks. As well as exploring the AMSD entries, supervised students will build on the existing corpus of 71 digitised paper sources and 1010 pre-vetted Trove records about message sticks, while independently investigating other materials relevant to their specific topics.

For more information see Postgraduate research opportunities with the Australian Message Stick project.